The evolution of healthcare incentives and higher quality care delivery at lower cost is no longer just a future reality. This priority has found its way into existing operations or near-term plans for hospitals, providers, and payers. Health care organizations preparing for delivery of what seems to be a mutually exclusive set of objectives are quickly realizing that they are not able to achieve those goals alone. Collaboration is required to deliver quality care at lower cost across the continuum of care, whether outpatient, inpatient, post-acute, or preventive care settings.

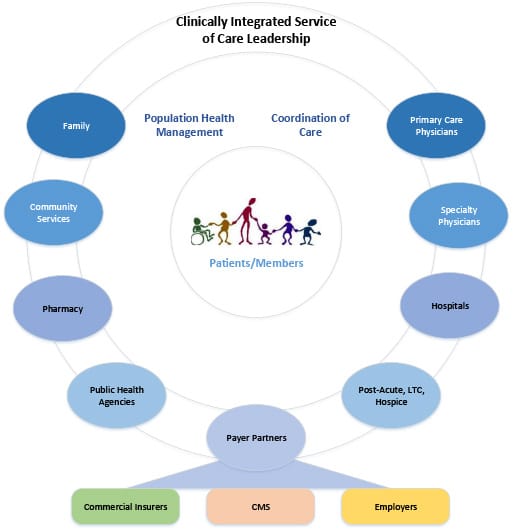

Clinically integrated systems of care (Figure 1) have emerged, and, despite having unique differences, all share some common goals. Three such collaboration models are accountable care organizations (ACO), clinical integration (CI) or clinically integrated networks (CIN), and patient-centered medical homes (PCMH).

Figure 1: Clinically Integrated Service of Care Leadership

Accountable care organization (ACO): An ACO is generally made up of a group of health care providers, typically primary care physicians, specialty physicians, post-acute, payers, and employers in some instances, who share responsibility for the care of identified patient or member populations. Demonstration of lowered costs and improved quality is required by CMS annually to participate in shared savings via additional reimbursements from CMS. Improved quality is clearly defined by CMS with 33 measures that span Patient/Caregiver Experience, Care Coordination/Patient Safety, Preventive Health, and At-Risk Population domains.

Clinical Integration (CI): CI is focused on bringing together independent primary care and specialty physicians into a network that is committed to higher quality of care delivery to their patients at lower cost. CI allows physicians to do this in a way that provides some protection from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and antitrust/monopolization law.

Clinical integrated networks (CIN) are typically governed by a physician-led body, which first establishes a set of clinical and cost metrics that define the core of the network’s performance goals. The governance body monitors and administers the entry and exit of physicians in the network to ensure that they maintain a network of physicians who are continuously meeting and advancing the overall network’s performance.

Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMH): PCMHs are typically focused on extending primary care beyond just the primary care physician and to a care team that can improve the overall quality of care, although some variation exists. A PCMH encourages patient engagement in their own care through access to a broader set of both clinical and cost information to help them work with their care team to make more informed decisions. The patient has additional access to preventive care and is frequently engaged by members of the care team to monitor things like diet, exercise, medications, and various appointments, as well as assisting with questions related to bills and benefits.

Clinically integrated systems of care offer alternatives for growing existing care delivery markets or expanding into new markets. Growth through mergers or acquisitions is another potential approach. In many cases, these clinically integrated systems of care yield provider, patient, and member experiences that feel more authentic than traditional care delivery as a result of collaboration and common goals and objectives. Granted, these newer system models require breaking down some long-standing barriers between hospitals, physicians, and payers, and requires a higher level of transparent yet secure access to data. Rapidly changing healthcare dynamics are driving a higher level of need for all providers of care to respond. Over time, those organizations opting for the status quo of today will more than likely be cut out of clinically integrated systems of care in the future.