Much of healthcare conversation during the last several months has included population health management and evidence-based outcomes. There are several vendors and systems providers that indicate that they have the capabilities, features, and functions to deliver solutions for these health management needs. Indeed, the clinical decision-making included in population health management and derivation of evidence-based outcomes needs to be powered by information that must be gleaned from multiple data sources surrounded by clinical, quality, patient demographic, social/economic, and other analytics capabilities. In addition, these must be easily accessed and interpreted by clinical, quality, and administrative workforces in a way that helps lead to both predictive and prescriptive decision support.

What frequently is not getting discussed is the great deal of process, procedure, policy, and people preparatory work that must be undertaken to ensure that evidence-based outcomes and population health management programs are successful. Frankly, a bit of Six Sigma-like thinking comes in handy in these discussions. That background and experience leads to asking questions about where there is variability in any process, and asking all of the “why” questions related to why there is variability in a process. Consider evidence-based outcomes. Leaving the IT-required infrastructure, data aggregation, and analytical needs out of this conversation for a moment, what else must be in place to produce valid evidence-based outcomes?

How about things such as:

- consistently applied standard treatment protocols and care pathways across the care continuum,

- transition of care workflow improvements,

- open, transparent, and timely sharing of information across care settings,

- person-centered cultures, and

- training, education, and coaching programs for patients, providers, and other care givers (e.g. family members)?

Variation in one or more of these may likely lead to variation in outcomes. The Eastern Association for The Surgery of Trauma wrote, “Evidence about the most effective methods of changing clinician behavior can be incorporated into disease management programs and thus, clinical and economic outcomes can be improved by reducing variation around optimal practice.”

Consider a diabetic who enters a diabetes program that starts with a controlled assessment of treatments and outcomes in an acute setting. At the end of three weeks, the patient has stabilized A1c, blood pressure, pulse, diet, weight, water retention, medications, leg and foot coloration and circulation, and other associated indicators. If they are then released into their PCP and Endocrinologist care with each prescribing care based upon their own adopted treatment plan, outcomes may likely be inconclusive as there was variability introduced into the overall process. Standards and processes must be developed and people must be trained and coached to mitigate and eliminate the introduction of variation into the process. These new standards and processes must also follow the patient as they move along the care settings: PCP to Specialist, Specialist to Acute, Acute to Post-Acute, and Post-Acute back to PCP. Any care setting may identify an evidence-based change to the care pathway or personal care plan, but then that change must be consistently understood, adopted, and followed by all providers in the continuum of care. This holds true for the home setting of the patient, and improvements are being made through telemedicine and care management processes to identify patient adherence to established care plans. The home environment is a major source for variation being introduced into evidence-based outcomes.

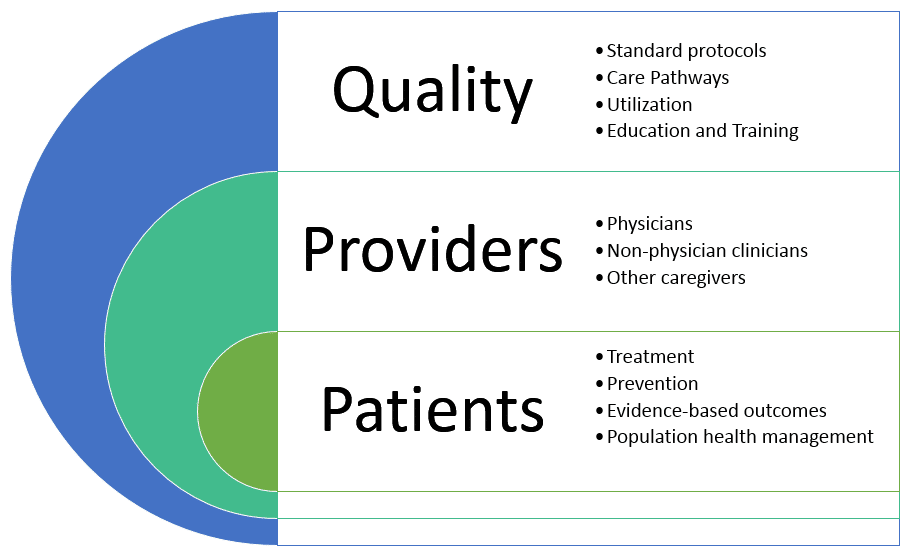

The diagram above is a simple illustration of people and process relationships in healthcare. People are the focus of medical outcomes. Patients are at the center and must be supported for all conditions; prevention for the health and getting healthy, acute, post-acute and recovery, and palliative for comfort. Physicians, non-physician clinicians, and other caregivers carry out the quality processes in the form of treatment protocols, procedures, care pathways, proper utilization, etc. Comparing the value and benefits of any program and practice requires evaluation of the process or processes supporting the program and practice. This applies as well to evidence-based outcomes and population health management. The value and quality of the outcomes must be partially evaluated based upon the underlying quality and consistency of the clinical quality, provider engagement, and physician engagement processes.

Perhaps a better starting point with systems and IT solutions providers is asking about their capability to help identify where variation is being introduced in existing clinical protocols, workflows, care pathways, and other care delivery points in the continuum. In the meantime, let’s not forget the criticality around change management as it applies to process, procedure, and policy standardization, and solid and consistent training of people.

References

The Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, https://www.east.org.